|

Hypertriglyceridemia

may actually be an acute phase reactant in the

plasma

......................................................................................................................................................................

Mehmet Rami

Helvaci (1)

Mursel Davarci

(2)

Orhan Veli Ozkan

(3)

Ersan Semerci

(3)

Abdulrazak Abyad

(4)

Lesley Pocock

(5)

(1) Specialist of Internal

Medicine, M.D.

(2) Specialist of Urology, M.D.

(3) Specialist of General Surgery, M.D.

(4) Middle-East Academy for Medicine of Aging,

Chairman, M.D., MPH, MBA, AGSF

(5) medi+WORLD International

Correspondence:

Mehmet Rami Helvaci, M.D.

07400, ALANYA, Turkey

Phone: 00-90-506-4708759

Email: mramihelvaci@hotmail.com

|

ABSTRACT

Background: We tried to understand whether

or not there is a significant relationship

between cholelithiasis or cholecystectomy

and plasma lipids.

Methods: The study was performed in

Internal Medicine Polyclinics on routine

check up patients. All cases either with

cholelithiasis or cholecystectomy for cholelithiasis

were put into the first, and age and sex-matched

control cases were put into the second groups.

Results: One hundred and forty-four

cases either with cholelithiasis or cholecystectomy

for cholelithiasis were detected among 3,437

cases, totally (4.1%). One hundred and sixteen

(80.1%) of them were females with a mean

age of 53.6 years. Obesity (54.8% versus

43.7%, p<0.01), body mass index (BMI)

(31.0 versus 28.9 kg/m2, p<0.01), and

hypertension (26.3% versus 13.1%, p<0.001)

were significantly higher in the cholelithiasis

or cholecystectomy group. Although the prevalence

of hyperbetalipoproteinemia was significantly

lower in the cholelithiasis or cholecystectomy

group (9.7% versus 18.0%, p<0.05), hypertriglyceridemia

(25.0% versus 18.0%, p<0.05) was significantly

higher in them.

Conclusions: There are significant relationships

between cholelithiasis and parameters of

the metabolic syndrome including age, female

sex, BMI, obesity, hypertension, and hypertriglyceridemia,

so cholelithiasis may also be found among

the terminal consequences of the metabolic

syndrome. Although the significantly lower

prevalence of hyperbetalipoproteinemia is

probably due to the decreased amount of

bile acids secreted during entrance of food

into the duodenum and decreased amount of

cholesterol absorbed in patients with cholelithiasis

or cholecystectomy, the higher prevalence

of hypertriglyceridemia may actually indicate

its primary role as an acute phase reactant

in the plasma.

Key words: Hypertriglyceridemia, metabolic

syndrome, acute phase reactant, cholelithiasis,

cholecystectomy

|

Chronic endothelial damage may

be the most common kind of vasculitis and the

leading cause of aging, morbidity, and mortality

in human beings (1, 2). Much higher blood pressure

(BP) of the afferent vasculature may be the major

underlying cause by inducing recurrent injuries

on endothelium, and probably whole afferent vasculature

including capillaries are involved in the process.

Thus the term of venosclerosis is not as famous

as atherosclerosis in the literature. Secondary

to the chronic endothelial inflammation, edema,

and fibrosis, vascular walls become thickened,

their lumens are narrowed, and they lose their

elastic natures that reduce blood flow to terminal

organs and increase systolic BP further. Some

of the well-known causes and indicators of the

inflammatory process are sedentary life style,

animal-rich diet, overweight, smoking, alcohol,

hypertriglyceridemia, hyperbetalipoproteinemia,

dyslipidemia, impaired fasting glucose, impaired

glucose tolerance, white coat hypertension, and

chronic inflammatory processes including rheumatologic

disorders, chronic infections, and cancers for

the development of terminal complications including

obesity, hypertension, diabetes mellitus (DM),

cirrhosis, peripheric artery disease (PAD), chronic

obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), chronic

renal disease (CRD), coronary artery disease (CAD),

mesenteric ischemia, osteoporosis, and stroke,

all of which terminate with early aging and premature

death. Although early withdrawal of causative

factors may prevent irreversible complications,

after development of cirrhosis, COPD, CRD, CAD,

PAD, or stroke, endothelial changes cannot be

reversed completely due to the fibrotic natures

of them. The accelerator factors and terminal

consequences were researched under the titles

of metabolic syndrome, aging syndrome, or accelerated

endothelial damage syndrome in the literature,

extensively (3-6). On the other hand, gallstones

are also found among one of the most common health

problems in developed countries (7), and they

are particularly frequent in women above the age

of 40 years (8). Most of the gallstones are found

in the gallbladder with the definition of cholelithiasis.

Its pathogenesis is uncertain and appears to be

influenced by genetic and environmental factors

(9). Excess weight is a well-known and age-independent

risk factor for cholelithiasis (10). Delayed bladder

emptying, decreased small intestinal motility,

and sensitivity to cholecystokinin were associated

with obesity and cholelithiasis (11). An increased

risk was confirmed in obese diabetics with hypertriglyceridemia

(12), and plasma cholesterol levels were also

found related with cholelithiasis (13). We tried

to understand whether or not there is a significant

relationship between cholelithiasis or cholecystectomy

and plasma lipids.

The study was performed in Internal

Medicine Polyclinics of the Dumlupinar and Mustafa

Kemal Universities on routine check up on patients

between August 2005 and November 2007. We took

consecutive patients below the age of 70 years

to avoid debility induced weight loss in elders.

Their medical histories including smoking habit,

hypertension, DM, dyslipidemia, and already used

medications and performed operations were learnt,

and a routine check up procedure including fasting

plasma glucose (FPG), triglyceride, high density

lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), low density lipoprotein

cholesterol (LDL-C), and an abdominal ultrasonography

was performed. Patients with devastating illnesses

including type 1 DM, malignancies, acute or chronic

renal failure, chronic liver diseases, hyper-

or hypothyroidism, and heart failure were excluded

to avoid their possible effects on weight. Current

daily smokers at least for the last six months

and cases with a history of five pack-years were

accepted as smokers. Cigar or pipe smokers were

excluded. Body mass index (BMI) of each case was

calculated by the measurements of the Same Physician

instead of verbal expressions since there is evidence

that heavier individuals systematically underreport

their weight (14). Weight in kilograms is divided

by height in meters squared, and underweight is

defined as a BMI value of lower than 18.5, normal

weight as lower than 24.9, overweight as lower

than 29.9, and obesity as 30.0 kg/m2 or greater

(15). Cases with an overnight FPG level of 126

mg/dL or greater on two occasions or already receiving

antidiabetic medications were defined as diabetics

(15). An oral glucose tolerance test with 75-gram

glucose was performed in cases with a FPG level

between 110 and 125 mg/dL, and diagnosis of cases

with a 2-hour plasma glucose level 200 mg/dL or

higher is DM (15). Patients with dyslipidemia

were detected, and we used the National Cholesterol

Education Program Expert Panel's recommendations

for defining dyslipidemic subgroups (15). Dyslipidemia

is diagnosed when LDL-C is 160 or higher and/or

triglyceride is 200 or higher and/or HDL-C is

lower than 40 mg/dL. Office BP was checked after

a 5-minute of rest in seated position with a mercury

sphygmomanometer on three visits, and no smoking

was permitted during the previous 2 hours. A 10-day

twice daily measurement of blood pressure at home

(HBP) was obtained in all cases, even in normotensives

in the office due to the risk of masked hypertension

after a 10-minute education about proper BP measurement

techniques (16). The education included recommendation

of upper arm while discouraging wrist and finger

devices, using a standard adult cuff with bladder

sizes of 12 x 26 cm for arm circumferences up

to 33 cm in length and a large adult cuff with

bladder sizes of 12 x 40 cm for arm circumferences

up to 50 cm in length, and taking a rest at least

for a period of 5 minutes in the seated position

before measurement. An additional 24-hour ambulatory

BP monitoring was not required due to the equal

efficacy of the method with HBP measurement to

diagnose hypertension (17). Eventually, hypertension

is defined as a BP of 135/85 mmHg or greater on

HBP measurements (16). Cholelithiasis was diagnosed

ultrasonographically. Eventually, all cases either

with presenting cholelithiasis or cholecystectomy

for cholelithiasis were put into the first and

age and sex-matched control cases were put into

the second groups. The mean BMI values and prevalences

of smoking, normal weight, overweight, obesity,

hypertension, DM, hypertriglyceridemia, hyperbetalipoproteinemia,

and dyslipidemia were compared between the two

groups. Mann-Whitney U test, Independent-Samples

t test, and comparison of proportions were used

as the methods of statistical analyses.

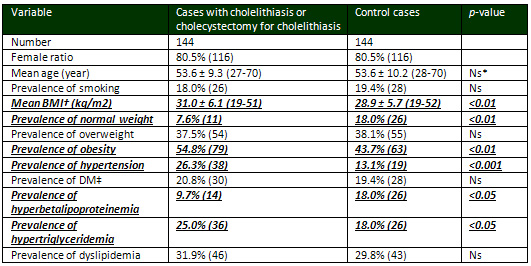

Although the exclusion criteria,

25 cases with already presenting asymptomatic

cholelithiasis and 119 cases with cholecystectomy

for cholelithiasis were detected among 3.437 cases,

totally (4.1%). One hundred and sixteen (80.1%)

of them were females with a mean age of 53.6 years,

so cholelithiasis is mainly a disorder of females

in their fifties. Prevalences of smoking were

similar in the cholelithiasis and control groups

(18.0% versus 19.4%, p>0.05, respectively).

Interestingly, 92.3% (133 cases) of the cholelithiasis

group had excess weight and only 7.6% (11 cases)

of them had normal weight. There was not any patient

with underweight among the study cases. Obesity

was significantly higher (54.8% versus 43.7%,

p<0.01) and normal weight was significantly

lower (7.6% versus 18.0%, p<0.01) in the cholelithiasis

group. Mean BMI values were 31.0 and 28.9 kg/m2,

(p<0.01) in the two groups. Probably parallel

to the higher mean BMI values, prevalence of hypertension

(26.3% versus 13.1%, p<0.001) was also higher

in the cholelithiasis group, significantly. Although

the prevalences of DM (20.8% versus 19.4%, p>0.05)

and dyslipidemia (31.9% versus 29.8%, p>0.05)

were also higher in the cholelithiasis groups,

differences were nonsignificant probably due to

the small sample sizes of the groups. Although

the prevalence of hyperbetalipoproteinemia was

significantly lower in the cholelithiasis or cholecystectomy

group (9.7% versus 18.0%, p<0.05), hypertriglyceridemia

(25.0% versus 18.0%, p<0.05) was significantly

higher in them (Table 1).

Table 1: Comparison of

cases with and without cholelithiasis

*Nonsignificant (p>0.05)

†Body mass index ‡Diabetes mellitus

Bile is formed in the liver as

an isosmotic solution of bile acids, cholesterol,

phospholipids, bilirubin, and electrolytes. The

liver synthesizes water-soluble bile acids from

water-insoluble cholesterol. About 50% of bile

secreted during the fasting state passes into

the gallbladder via the cystic duct. So gallbladder

filling is facilitated during fasting. Up to 90%

of water in the gallbladder bile is absorbed as

an electrolyte solution, so bile acids are concentrated

in the gallbladder and little amount of bile flows

from the liver during fasting. Food entering the

duodenum stimulates gallbladder contraction, releasing

much of the body pool of bile acids to mix with

food content and perform its several functions

including solubilization of dietary cholesterol,

fats, and fat-soluble vitamins to facilitate their

absorption in the form of mixed micelles, causing

water secretion by the colon promoting catharsis,

excretion of bilirubin as degradation products

of heme compounds from worn-out red blood cells,

excretion of drugs and ions from the body, and

secretion of various proteins important for the

gastrointestinal functions. About 90% of bile

acids is reabsorbed by the terminal ileum into

the portal system. Bile salts

are efficiently extracted by the liver, and secreted

back into bile, so bile acids undergo enterohepatic

circulation 10 to 12 times per day. The most clinical

disorders of the extrahepatic biliary tract are

related with the gallstones. In the USA, 20% of

people above the age of 65 years have gallstones,

and each year more than 500,000 patients undergo

cholecystectomy. Factors increasing the probability

of gallstones include age, female sex, and obesity.

Highly water-insoluble cholesterol is the major

component of most gallstones. Biliary cholesterol

is solubilized in the bile salt-phospholipid micelles

and phospholipid vesicles. The amount of cholesterol

carried in micelles and vesicles varies with the

bile salt secretion rate. In another perspective,

cholelithiasis may actually be a natural defence

mechanism of the body to decrease amount of bile

acids secreted during entrance of food into the

duodenum and decrease amount of cholesterol absorbed.

Similarly, bile acid sequestrants including cholestyramine

and cholestipol effectively lower serum LDL-C

by binding bile acids in intestine and interrupting

enterohepatic circulation of them.

Excess weight leads to both structural

and functional abnormalities of many systems of

the body. Recent studies revealed that adipose

tissue produces leptin, tumor necrosis factor-alpha,

plasminogen activator inhibitor-1, adiponectin,

and other cytokines which act as acute phase reactants

in the plasma (18, 19). For example, the cardiovascular

field has recently shown a great interest in the

role of inflammation in the development of atherosclerosis

and numerous studies indicated that inflammation

plays a significant role in the pathogenesis of

atherosclerosis and thrombosis (1, 2). On the

other hand, individuals with excess weight have

an increased blood volume as well as an increased

cardiac output thought to be the result of increased

oxygen demand of the excessive fat tissue. The

prolonged increase in blood volume can lead to

myocardial hypertrophy and decreased compliance

in addition to the common comorbidity of hypertension.

In addition to them, the prevalences of high FPG,

high serum total cholesterol, and low HDL-C increased

parallel to the higher BMI values (20). Combination

of these cardiovascular risk factors will eventually

lead to an increase in left ventricular stroke

with higher risks of arrhythmias, cardiac failure,

and sudden cardiac death. Similarly, the prevalences

of CAD and stroke increased parallel with the

higher BMI values in some other studies (20, 21),

and risk of death from all causes including cancers

increased throughout the range of moderate to

severe weight excess in all age groups (22). As

another consequence of excess weight on health,

cholelithiasis cases had a significantly higher

BMI value in the present study (31.0 versus 28.9

kg/m2, p<0.01) similar to some other reports

(8, 9). Probably as a consequence of the higher

BMI values, the prevalences of hypertension (26.3%

versus 13.1%, p<0.001) and hypertriglyceridemia

(25.0% versus 18.0%, p<0.05) were also higher

in the cholelithiasis group. The relationships

between excess weight and elevated BP and hypertriglyceridemia

were described in the metabolic syndrome (23),

and clinical manifestations of the syndrome included

obesity, dyslipidemia, hypertension, insulin resistance,

and proinflammatory and prothrombotic states (24).

The increased risk of cholelithiasis in obese

diabetics with hypertriglyceridemia may also be

an indicator of its association with the metabolic

syndrome (10, 23). Similarly, prevalences of smoking

(42.2% versus 28.4%, p<0.01), excess weight

(83.6% versus 70.6%, p<0.01), DM (16.3% versus

10.3%, p<0.05), and hypertension (23.2% versus

11.2%, p<0.001) were all higher in the hypertriglyceridemia

cases in another study (25). It is a well-known

fact that smoking causes a chronic inflammatory

process in the respiratory tract, lungs, and vascular

endothelium all over the body terminating with

an accelerated atherosclerosis, end-organ insufficiencies,

early aging, and premature death thus it should

be included among the major parameters of the

metabolic syndrome. On the other hand, smoking-induced

weight loss is probably related with the smoking-induced

endothelial inflammation all over the body since

loss of appetite is one of the main symptoms of

disseminated inflammation in the body. In another

explanation, smoking-induced loss of appetite

is an indicator of being ill instead of being

healthy during smoking (26-28). Buerger's disease

(thromboangiitis obliterans) alone is also a clear

evidence to show the strong atherosclerotic effects

of smoking since this disease has not been shown

in the absence of smoking up to now. On the other

hand, as a parallel finding to the present study,

the prevalences of hyperbetalipoproteinemia were

similar in the hypertriglyceridemia and control

groups (18.9% versus 16.3%, p>0.05, respectively)

in the above study (25).

Although the mean age, female

sex, BMI, obesity, hypertension, and hypertriglyceridemia

indicated significant differences in the cholelithiasis

or cholecystectomy group in the present study,

there was no significant difference for the lipid

parameters in another study (29). Whereas total

cholesterol, triglycerides, and LDL-C were significantly

reduced in patients on day 3 of surgery and 6

months after the cholecystectomy in another one

(30). Similar to our results, significantly higher

prevalence of cholelithiasis was found in patients

with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)

(47% versus 26%, p<0.0001), and type 2 DM,

overweight, obesity, and cholelithiasis were identified

as independent predictors of NAFLD (31). Fifty

six percent of patients with cholelithiasis had

NAFLD compared with 33% of patients without (p<0.0001)

(31). Age above 50 years, triglycerides above

1.7 mmol/l, overweight, obesity, and total cholesterol

concentration were the independent predictors

of cholelithiasis (31). So NAFLD may represent

a pathogenetic link between the metabolic syndrome

and cholelithiasis (31). Similarly, patients with

type 2 DM had higher probability of having cholelithiasis,

and age, female sex, and BMI were independently

associated with cholelithiasis (32). Obesity may

lead to fatty infiltration causing organ dysfunctions,

and the higher BMI values were associated with

steatocholecystitis in another study (33). As

an opposite finding to our results, serum LDL-C

values of patients with cholelithiasis above the

age of 40 years were significantly elevated (p<0.05)

in another one (34).

Although ATP II determined

the normal triglyceride value as lower than 200

mg/dL (35), WHO in 1999 (36) and ATP III in 2001

(13) reduced this normal limit as lower than 150

mg/dL. Although these cutpoints are usually used

to define limits of the metabolic syndrome, whether

or not more lower limits provide additional benefits

for human beings is unclear. In a previous study,

patients with a triglyceride value lower than

60 mg/dL were collected into the first, lower

than 100 mg/dL into the second, lower than 150

mg/dL into the third, lower than 200 mg/dL into

the fourth, and equal to or greater than 200 mg/dL

were collected into the fifth groups, respectively

(23). Prevalence of smoking was the highest in

the fifth group which may also indicate inflammatory

roles of smoking and hypertriglyceridemia in the

metabolic syndrome. The mean body weight increased

continuously, parallel to the increasing value

of triglyceride. As the most surprising result,

the prevalences of hypertension, type 2 DM, and

CAD, as some of the terminal end points of the

metabolic syndrome, showed their most significant

increases after the triglyceride value of 100

mg/dL (23). As one of our opinion, significantly

increased mean age by the increased triglyceride

values may be secondary to aging induced decreased

physical and mental stresses, which eventually

terminates with onset of excess weight and other

parameters and terminal end points of the metabolic

syndrome. Interestingly, the mean age increased

from the lowest triglyceride having group towards

the triglyceride value of 200 mg/dL, then decreased.

The similar trend was also seen in the mean LDL-C

and BMI values, and prevalence of WCH. These trends

may be due to the fact that although the borderline

high triglyceride values (150-199 mg/dL) is seen

together with overweight, obesity, physical inactivity,

smoking, and alcohol like acquired causes, the

high triglyceride (200-499 mg/dL) and very high

triglyceride values (500 mg/dL and higher) are

usually secondary to both acquired and secondary

causes such as type 2 DM, chronic renal failure,

and genetic patterns (13). But although the underlying

causes of the high and very high triglyceride

values may be a little bit different, probably

risks of the terminal end points of the metabolic

syndrome do not change in these groups, too. For

example, prevalences of hypertension and type

2 DM were the highest in the highest triglyceride

value having group in the above study (23). Eventually,

although some authors reported that lipid assessment

in vascular disease can be simplified by measurement

of either total and HDL-C levels without the need

of triglyceride (37), the present study and most

others indicated a causal association between

triglyceride-mediated pathways and parameters

of the metabolic syndrome (38). Similarly, another

study indicated moderate and highly significant

associations between triglyceride values and CAD

in Western populations (39).

As a conclusion, there are significant relationships

between cholelithiasis and parameters of the metabolic

syndrome including age, female sex, BMI, obesity,

hypertension, and hypertriglyceridemia, so cholelithiasis

may also be found among the terminal consequences

of the metabolic syndrome. Although the significantly

lower prevalence of hyperbetalipoproteinemia is

probably due to the decreased amount of bile acids

secreted during entrance of food into the duodenum

and decreased amount of cholesterol absorbed in

patients with cholelithiasis or cholecystectomy,

the higher prevalence of hypertriglyceridemia

may actually indicate its primary role as an acute

phase reactant in the plasma.

1. Widlansky ME, Gokce N, Keaney JF Jr, Vita JA.

The clinical implications of endothelial dysfunction.

J Am Coll Cardiol 2003; 42: 1149-1160.

2. Ridker PM. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein:

Potential adjunct for global risk assessment in

the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease.

Circulation 2001; 103: 1813-1818.

3. Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ. The metabolic

syndrome. Lancet 2005; 365: 1415-1428.

4. Helvaci MR, Kaya H, Sevinc A, Camci C. Body

weight and white coat hypertension. Pak J Med

Sci 2009; 25: 6: 916-921.

5. Helvaci MR, Aydin LY, Aydin Y. Digital clubbing

may be an indicator of systemic atherosclerosis

even at microvascular level. HealthMED 2012; 6:

3977-3981.

6. Helvaci MR, Aydin Y, Gundogdu M. Atherosclerotic

effects of smoking and excess weight. J Obes Wt

Loss Ther 2012; 2: 7.

7. Tazuma S. Gallstone disease: Epidemiology,

pathogenesis, and classification of biliary stones

(common bile duct and intrahepatic). Best Pract

Res Clin Gastroenterol 2006; 20: 1075-1083.

8. Katsika D, Grjibovski A, Einarsson C, Lammert

F, Lichtenstein P, Marschall HU. Genetic and environmental

influences on symptomatic gallstone disease: a

Swedish study of 43,141 twin pairs. Hepatology

2005; 41: 1138-1143.

9. Lammert F, Sauerbruch T. Mechanisms of disease:

the genetic epidemiology of gallbladder stones.

Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol 2005; 2:

423-433.

10. Erlinger S. Gallstones in obesity and weight

loss. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2000; 12: 1347-1352.

11. Mathus-Vliegen EM, Van Ierland-Van Leeuwen

ML, Terpstra A. Determinants of gallbladder kinetics

in obesity. Dig Dis Sci 2004; 49: 9-16.

12. Fraquelli M, Pagliarulo M, Colucci A, Paggi

S, Conte D. Gallbladder motility in obesity, diabetes

mellitus and coeliac disease. Dig Liver Dis 2003;

35: 12-16.

13. Devesa F, Ferrando J, Caldentey M, Borghol

A, Moreno MJ, Nolasco A, et al. Cholelithiasic

disease and associated factors in a Spanish population.

Dig Dis Sci 2001; 46: 1424-1436.

14. Bowman RL, DeLucia JL. Accuracy of selfreported

weight: a meta-analysis. Behav Ther 1992; 23:

637-635.

15. Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education

Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation,

and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults

(Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation

2002; 106: 3143-3421.

16. O'Brien E, Asmar R, Beilin L, Imai Y, Mallion

JM, Mancia G, et al. European Society of Hypertension

recommendations for conventional, ambulatory and

home blood pressure measurement. J Hypertens 2003;

21: 821-848.

17. Helvaci MR, Seyhanli M. What a high prevalence

of white coat hypertension in society! Intern

Med 2006; 45: 671-674.

18. Funahashi T, Nakamura T, Shimomura I, Maeda

K, Kuriyama H, Takahashi M, et al. Role of adipocytokines

on the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis in visceral

obesity. Intern Med 1999; 38: 202-206.

19. Yudkin JS, Stehouwer CD, Emeis JJ, Coppack

SW. C-reactive protein in healthy subjects: associations

with obesity, insulin resistance, and endothelial

dysfunction: a potential role for cytokines originating

from adipose tissue? Arterioscler Thromb Vasc

Biol 1999; 19: 972-978.

20. Zhou B, Wu Y, Yang J, Li Y, Zhang H, Zhao

L. Overweight is an independent risk factor for

cardiovascular disease in Chinese populations.

Obes Rev 2002; 3: 147-156.

21. Zhou BF. Effect of body mass index on all-cause

mortality and incidence of cardiovascular diseases

- report for meta-analysis of prospective studies

open optimal cut-off points of body mass index

in Chinese adults. Biomed Environ Sci 2002; 15:

245-252.

22. Calle EE, Thun MJ, Petrelli JM, Rodriguez

C, Heath CW Jr. Body-mass index and mortality

in a prospective cohort of U.S. adults. N Engl

J Med 1999; 341: 1097-1105.

23. Helvaci MR, Kaya H, Gundogdu M. Association

of increased triglyceride levels in metabolic

syndrome with coronary artery disease. Pak J Med

Sci 2010; 26: 667-672.

24. Tonkin AM. The metabolic syndrome(s)? Curr

Atheroscler Rep 2004; 6: 165-166.

25. Helvaci MR, Aydin LY, Maden E, Aydin Y. What

is the relationship between hypertriglyceridemia

and smoking? Middle East J Age and Ageing 2011;

8: 6.

26. Hughes JR, Hatsukami DK. Effects of three

doses of transdermal nicotine on post-cessation

eating, hunger and weight. J Subst Abuse 1997;

9: 151-159.

27. Miyata G, Meguid MM, Varma M, Fetissov SO,

Kim HJ. Nicotine alters the usual reciprocity

between meal size and meal number in female rat.

Physiol Behav 2001; 74: 169-176.

28. Laaksonen M, Rahkonen O, Prattala R. Smoking

status and relative weight by educational level

in Finland, 1978-1995. Prev Med 1998; 27: 431-437.

29. Cojocaru C, Pandele GI. Metabolic profile

of patients with cholesterol gallstone disease.

Rev Med Chir Soc Med Nat Iasi 2010;114: 677-682.

30. Malik AA, Wani ML, Tak SI, Irshad I, Ul-Hassan

N. Association of dyslipidaemia with cholilithiasis

and effect of cholecystectomy on the same. Int

J Surg 2011; 9: 641-642.

31. Koller T, Kollerova J, Hlavaty T, Huorka M,

Payer J. Cholelithiasis and markers of nonalcoholic

fatty liver disease in patients with metabolic

risk factors. Scand J Gastroenterol 2012; 47:

197-203.

32. Sodhi JS, Zargar SA, Khateeb S, Showkat A,

Javid G, Laway BA, et al. Prevalence of gallstone

disease in patients with type 2 diabetes and the

risk factors in North Indian population: a case

control study. Indian J Gastroenterol 2014; 33:

507-511.

33. Yoon JH, Kim YJ, Baik GH, Kim YS, Suk KT,

Kim JB, et al. The Impact of Body Mass Index as

a Predictive Factor of Steatocholecystitis. Hepatogastroenterology

2014; 61: 902-907.

34. Batajoo H, Hazra NK. Analysis of serum lipid

profile in cholelithiasis patients. J Nepal Health

Res Counc 2013; 11: 53-55.

35. National Cholesterol Education Program. Second

report of the expert panel on detection, evaluation,

and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults

(Adult Treatment Panel II). Circulation 1994;

89: 1333-1445.

36. World Health Organization. Definition, diagnosis

and classification of diabetes mellitus and its

complications. Report of a WHO consultation 1999.

37. Di Angelantonia E, Sarwar N, Perry P, Kaptoge

S, Ray KK, Thompson A, et al. Major lipids, apolipoproteins,

and risk of vascular disease. JAMA 2009; 302:

1993-2000.

38. Sarwar N, Sandhu MS, Ricketts SL, Butterworth

AS, Di Angelantonia E, Boekholdt SM, et al. Triglyceride-mediated

pathways and coronary disease: collaborative analysis

of 101 studies. Lancet 2010; 375: 1634-1639.

39. Sarwar N, Danesh J, Eiriksdottir G, Sigurdsson

G, Wareham N, Bingham S, et al. Triglycerides

and the risk of coronary heart disease: 10,158

incident cases among 262,525 participants in 29

Western prospective studies. Circulation 2007;

115: 450-458.

|