|

Prevention of

Otologic disorders in Nigeria: The Case of Primary

School Children in Rivers State, South South of

Nigeria

......................................................................................................................................................................

Nduka, Ijeoma (1)

Enwereji, Ezinna Ezinne (2)

Aitafo, Josephine Enekole (3)

(1) Nduka, Ijeoma, Department

of Community Medicine,

Niger Delta University Wilberforce Island,

Amassoma Bayelsa state, Nigeria.

(2) Enwereji, Ezinna Ezinne, College of Medicine,

University Teaching Hospital,

Abia State University Uturu, Aba, Abia State,

Nigeria.

(3) Aitafo, Josephine Enekole

Braithwaite Memorial Specialist Hospital,

6, Haley Street, Off Forces Avenue, Old GRA,

Port Harcourt, Rivers State

Correspondence:

Enwereji, Ezinna Ezinne, College of Medicine,

University Teaching Hospital ,

Abia State University Uturu, Aba,

Abia State, Nigeria.

Email: hersng@yahoo.com

|

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Common ear diseases

in children are preventable. In developing

countries like Nigeria, most health care

programmes concentrate on secondary school

pupils to the disadvantage of those in primary

schools. This has delayed reduction of preventable

ear diseases. Ear diseases among children

can lead to disabilities especially permanent

hearing loss. The question is to what extent

are otologic disorders prevented among primary

school children? The researchers carried

out school health programmes to identify

common ear diseases in primary school children

so as to contribute a quota in prevention

of otologic diseases among them.

Materials and method: This was a

cross-sectional descriptive study. Random

sample of 1,200 pupils from primary 1-6

between 5 to 13 years were selected for

study from 13 primary schools. Only 802

pupils whose parents gave consent eventually

participated in this study. Administered

semi-structured questionnaire was used to

obtain information on participants from

parents. Also, otoscopic examination of

respondents was carried out by the researchers

after being trained in use of otoscope by

a specialist. Complete physical examination

of the 802 children was done. Cerumen was

recorded if no part of tympanic membrane

was visible.

Thereafter, cerumen, other debris and foreign

bodies were removed in such children. External

canals and tympanic membranes were inspected

for likely abnormalities. Data analyses

were done using SPSS version

17.0 statistical software. Results were

presented on tables using frequency and

percentages.

Results: Findings showed that out

of 802 children studied, only 279(34.8%)

were found normal.

The common Otologic diseases found among

the respondents were impacted cerumen 319(39.7%),

chronic suppurative otitis media 95 (11.8%),

debris 55 (6.9%), Otitis media with effusion

28 (3.5%), and acute otitis media 10 (1.3%).

Conclusion: Based on the proportion

of children identified with otologic problems,

there is need for periodic and well coordinated

school health programmes.

Key words: Otologic

disorders, school children, otitis media,

hyperemic.

|

The importance of prevention

of ear diseases as an organ of hearing cannot

be overemphasized. Disorders of the ear among

children in developing countries have been widely

reported as a major public health problem [1-6].

Delayed speech, cognitive, emotional, social and

academic developments have been reported as some

of the direct effects of hearing impairment in

children [7].Studies have shown that a good proportion

of children with ear diseases have difficulties

in learning and as a result, their academic performances

are negatively affected [8,9]. It is a well known

fact that with early medical intervention, disability

from diseases of the ear can be prevented. However,

most times children with ear problems are not

diagnosed early and as a result, the diseases

progress to profound deafness.

Ear disorders in children can arise from congenital

problems such as Crouzons's disease, Down's syndrome,

Achondroplasia or Marfan's disease and others

[10-12]. Ear disorders in children can also result

from acquired causes like otitis media with effusion

(OME), otitis externa, trauma leading to perforation

of the tympanic membrane or impacted cerumen [13,14].

There have been various views regarding the effect

of removing impacted cerumen (wax). Some researchers

argue that removing impacted cerumen (wax) prevents

hearing loss [15,16], while others emphasize that

there will be persistent hearing loss even after

the wax has been removed [17].

Studies have recommended a high index of suspicion

in the diagnosis of ear diseases among children.

This is necessary because most studies are of

the view that Otitis media constitute the main

ear disorder in children living in developing

countries including Nigeria [18-20]. Some authors

further argue that most ear disorders present

with or without symptoms and that only a thorough

history and physical examination of children with

ear problems would guarantee effective diagnosis,

treatment and prevention of disability. Such authors

recommended that physicians should conduct thorough

examination of the head and neck area of a child

for a possible predisposing factors to developing

ear diseases when a history of high grade fever,

pain in the ear, ear discharge, pre or post auricular

swelling, hearing impairment, deep seated headache,

dizziness, tinnitus and vertigo is reported [21-25].

WHO (2000) recommended that periodic screening

for hearing impairments in schools will ensure

early diagnosis and treatment for children with

ear diseases especially those in developing countries.

This is necessary because some ear diseases are

gradual in onset, painless, without signs and

symptoms and at times invisible (26). Therefore,

without routine screening of school children especially

in places where there is no working national guidelines,

the likelihood of detecting children with ear

disorders could go unnoticed until later in the

child's age when prevention becomes difficult

[27-29]. In developed countries, where neonates

were screened for diseases of the ear, studies

have reported a high proportion of neonates with

hearing impairment [30]. Prevention of ear diseases

in children requires follow-up for the purposes

of repeat audiology test and for intervention

after definitive diagnoses (31,32).

The benefits of screening school children for

disabilities especially hearing loss should not

be underestimated. In developing countries, like

Nigeria, children with disabilities are totally

dependent on others and as such, have little or

no contribution towards the economic development

of the country where they reside. The need to

ensure that youths live satisfying and fulfilled

lives devoid of disabilities and dependence motivated

the researchers to conduct this study. This research

enabled the researchers to contribute a quota

to the recent call for the prevention of disabilities

among school children in Nigeria. In this study,

the researchers emphasized the need to strengthen

routine ear screening from neonatal period to

school period, periodic physical examinations

and health education in schools. The study will

help to complement the limited studies on childhood

ear diseases in Nigeria.

This cross-sectional descriptive

study was carried out to identify common otologic

disorders among primary school children in Rivers

State. The sample was made up 1,200 pupils in

primary 1-6 within the ages of 5 to 13 years randomly

selected from 13 primary schools. This study was

conducted in Port-Harcourt City (PHC). Port-Harcourt

was chosen for the study because it is the capital

of Rivers State and the major oil-producing State

in Nigeria. It attracts lots of investors and

tourists from all parts of the country and beyond.

Moreover, Port-Harcourt has the largest number

of highly populated primary schools among the

23 local governments in the State and therefore

afforded enough sample for the study. The thirteen

(13) schools selected for study were based on

the fact that their populations were made up of

both boys and girls (co-educational). The sample

size was calculated at a 95% confidence level

for a 13.9% proportion of hearing loss among primary

school children in Lagos, Nigeria [20]. To get

the sample for study, simple random sampling by

balloting was used to select 1200 pupils from

classes 1-6. Only 802 pupils whose parents gave

consent eventually participated in this study.

Semi-structured self administered questionnaire

was used to obtain information on the participants

from the parents. Also questionnaire was used

to explore the social status of the parents of

the respondents. The social status of the respondents'

parents was graded into five ( 1-5) categories

based on their monthly income. In addition, otoscopic

examination of the respondents was carried out

by the researchers after being trained on the

use of otoscope by a specialist. Also, complete

physical examination on the 802 children was done

and cerumen was recorded if no part of the tympanic

membrane was visible. Thereafter, cerumen, other

debris and foreign bodies were removed in such

children. The external canals and tympanic membranes

were later inspected for likely abnormalities.

Children were classified as having abnormal ear

drums or having otitis media if the drums were

perforated, hyperemic, retracted or showed evidence

of scarring with or without fluids. Data analyses

were done using SPSS version 17.0 [21] statistical

software. Results were presented in tables using

frequency and percentages.

Ethical consideration

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Ethics

Committee of the University of Port Harcourt Teaching

Hospital. The consents of the Director Rivers

State Ministry of Education, the head teachers

in the 13 schools, and parent of the pupils selected

for study were obtained. Their permissions enabled

the researchers to commence the study. Only the

children whose parents gave consent were included

for study.

Limitations to the study

The population studied was school children therefore,

the observed prevalence of ear diseases w ould

not reflect the actual picture in the general

population because institutional based study may

not give a clear picture of the situation outside

the school.. Also children not in school as well

as those whose parents refused to consent to the

study might have epidemiological characteristics

different from those who took part in the study.

The cross-sectional descriptive design of the

study could not allow causality to be determined.

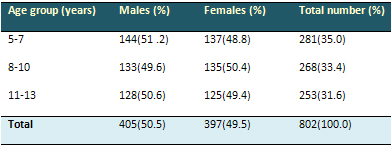

The mean age of the respondents

was 8.6 years ± 2.3 years with median 8.0

years. About 405(50.5%) males and 397(49.5%) females

were studied. The age of the respondents was evenly

distributed. About 281 (35.0%) pupils were between

the age of 5-7 years and 253 (31.6%) were between

11-13 years. See Table 1 for more details As contained

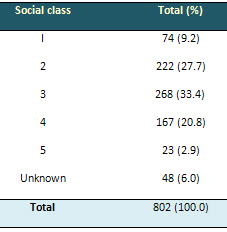

in Table 2, the social class of the parents of

the study group was classified into 5 categories

using their monthly income. Those in category

1 were on monthly income of USD 2890, category

2, USD 2312, category 3 on USD 1692, category

4 on USD 867 and category 5 were on USD 289. The

social status of 48(6.0%) of the respondents ,

could not be ascertained because enough information

was not provided by their parents/guardians. Study

showed that a good proportion of the respondents

268 (33.4%) came from social class category 3.

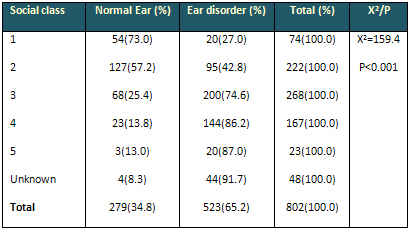

The social class of the parents of the respondents

who had more otologic disorders than others was

noted. From the result of the study, respondents

from social status category 5 had the highest

incidence of otologic disorders. This is statistically

significant P<0.001 see Table 3 for more details.

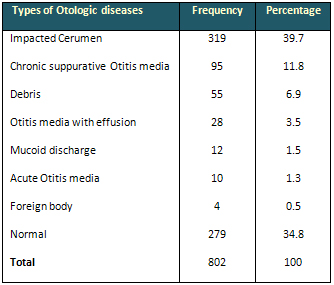

The types of otologic diseases seen among the

respondents were noted. From the findings, impacted

cerumen 319(39.7%), Chronic suppurative otitis

media 95(11.8%), debris 55(6.9%), Otitis media

with effusion 28(3.5%), and acute otitis media

10(1.3%) were noted. See Table 4 for more details.

Table 1: Age and Sex Distribution of Study Population

Table 2: Social Class of the Study Population

Table 3: Social status of the parents of respondents

and Otologic disorders

Table 4: Respondents and types of Otologic

diseases noted

From the result of this study,

several otologic diseases were identified among

the respondents after the otologic examination.

The most common otologic diseases was impacted

cerumen. The fact that impacted cerumen was the

most common otologic disease among the population

studied showed the extent to which the tympanic

membranes of the respondents were occluded as

well as the extent they are exposed to hearing

loss. Impacted cerumen occluding the tympanic

membrane has been widely reported by several researchers

as the major cause of hearing loss in children

[12, 26]. This finding is similar to studies conducted

in other parts of Nigeria [20, 23], Turkey [24]

and Swaziland [25] where impacted cerumen was

identified as the main otologic disease among

the population studied. Usually impacted cerumen

in children is asymptomatic and can easily be

missed by parents and caregivers. This could possibly

lead to hearing impairment in the affected children.

Identifying foreign bodies as the least otologic

disease among the respondents (0.5%) is comparable

to that identified by some other studies [26,

27]. It is not surprising that foreign bodies

constitute the least otologic disease among the

group studied. This is because foreign bodies

usually present some discomforting symptoms that

will demand immediate attention for their removal.

Chronic suppurative otitis media (CSOM) has been

implicated as the major risk factor for ear diseases

in children [28]. It has been seen as the major

health challenge in several parts of the world

[22, 28, 29 ]. The finding in this study reveals

a CSOM prevalence of 11.8%. This is low compared

to a study conducted by Akinpelu etal [30] in

which a prevalence as high as 33.9% was seen among

the population studied. This high prevalence noted

in the previous studies could be attributed to

the wider age group interval (6months to 18years)

that participated in the study

as against the present study which used (5years

to 13 years).

Social status was an important

factor in the occurrence of otologic diseases

among the group studied. The lower the respondents'

social status the more otologic diseases they

presented with. In this study, chronic suppurative

otitis media was high among social status categories

4 and 5 which had monthly income of USD 867 and

USD 289 respectively. Chronic suppurative otitis

media has been linked to poor hygiene, nutrition,

and housing conditions and these poor conditions

encourage viral and bacterial infections [29].

This finding is comparable to previous studies

which found higher prevalence of chronic suppurative

otitis media among African-Americans than Caucasians

[31]. This difference in the prevalence was attributed

to poor standard of living among African-Americans.

Most individuals in the low socio-economic class

avoid living in places where they will be expected

to pay high house rent and as a result, they tend

to prefer living in suburbs where house rents

are low but the environmental conditions are poor.

The fact that the respondents from the lowest

social status categories 4 and 5, whose monthly

income was poor presented with more otologic problems

than others, showed that low social status constitutes

a major risk factor for otologic diseases among

school children. The prevalence of otologic diseases

of 65.2% among school children as identified in

this study, is lower than that reported by other

researchers in a study conducted in Nepal where

a prevalence of 75.7% was noted [22]. The observed

difference in the two studies conducted could

be influenced by the socio-demographic variations

in the two populations studied.

In ranking the prevalence of acute otitis media

(AOM) among the respondents, AOM with 1.3% was

the sixth otologic disorder. This ranking is comparable

to a study conducted in Nepal [22 ] in which AOM

with 1.4% prevalence was ranked as the 4th otologic

disorder seen among the group studied. In another

study [32] the prevalence of AOM was 28% and ranked

higher than the two studies above. The difference

in this ranking might be in the population studied.

The sample studied here comprised children with

febrile illnesses. AOM is an acute illness that

commonly presents with other febrile illnesses

in children [8]. Most often, in developing countries

where malaria is endemic, children who present

with feverish conditions with no other symptoms

suggestive of any ear disease are treated for

malaria, thereby making clinicians miss AOM, except

if the clinician has a high index of suspicion

for ear disorders and this often will lead to

further delay in making the diagnosis. The fact

that some ear diseases are asymptomatic and could

be missed or given late diagnosis when prevention

may be unattainable, periodic physical examination

as well as health education is needed in primary

schools.

Since cerumen impaction which was associated with

low social status and poor environmental condition

was the commonest otologic problem seen in this

study , the need to prevent it by routine examination,

aural toileting or simple cleaning with cotton

buds to check reaccumulation is necessary. Parents,

care givers, and teachers should be health educated

on how to identify symptoms for ear diseases in

children. During health programmes in school,

clinicians should examine every child's ear for

a possible ear disease.

1. Eisenberg, L. S. . Johnson, K. C Martinez, A.

S. Visser- Dumont, L. Ganguly, D. H. and J. F. Still,

"Studies in pediatric hearing loss at the House

Research Institute," Journal of the American

Academy of Audiology, vol. 23, no. 6, pp. 412-421,2012.

2. Islam, M. A. Islam, M. S.

. Sattar, M. A and M. I. Ali, "Prevalence

and pattern of hearing loss," Medicine Today,

vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 18-21, 2012.

3. Sekhar, D. L Zalewski, T.

R. and I. M. Paul, "Variability of state

school-based hearing screening protocols in the

United States,"Journal of Community Health,

vol. 38, no. 3, pp. 569-574, 2013.

4. Byrne, D. C Themann, C. L.

Meinke, . D. K Morata, T. C. and M. R. Stephenson,

"Promoting hearing loss prevention in audiology

practice," Perspectives on Public Health

Issues Related to Hearing and Balance, vol. 13,

no. 1, pp. 3-19, 2012.

5. Uller, R. M¨G. Fleischer,

and J. Schneider, "Pure-tone auditory threshold

in school children," European Archives of

Oto-Rhino- Laryngology, vol. 269, no. 1, pp. 93-100,

2012.

6. Turton,L and P. Smith, "Prevalence &

characteristics of severe and profound hearing

loss in adults in a UK National Health Service

clinic," International Journal of Audiology,

vol. 52, no. 2, pp. 92-97, 2013.

7. Gell FM, White E, McNewell

K, Mackenzie I, Smith A, Thompson S et al. Practical

screening priorities for hearing impairment among

children in developing countries. Bull.

World Health Org. 1992, 70:645-55.

8. Hadda J. Hearing loss In:

Behrman RE, Kliegman RM, Jenson BH. Eds. Nelson

Textbook of Paediatrics, 17th ed. W.B Saunders

Company, Philadelphia 2004:2129-2135.

9. Adams DA. The causes of deafness.

In: Kerr AG, Adams DA, Michael J Eds. Scott-Brown's

Paediatric otolaryngology. 6th ed. Cinnammond

1997; 6:61-72.

10. Yiengprugsawan, V. Hogan,

A. and L. Strazdins, "Longitudinal analysis

of ear infection and hearing impairment: findings

from 6-year prospective cohorts of Australian

children," BMC

Pediatrics, vol. 13, no. 1, article 28, 2013.

11. Chadha, S.A. Sayal, V. Malhotra,

and A. Agarwal, "Prevalence of preventable

ear disorders in over 15 000 schoolchildren in

northern India," Journal of Laryngology &

Otology, vol. 127, no.1, pp. 28-32, 2013.

12. Olusanya B.O. Hearing impairment

in children with impacted cerumen. Annals of Tropical

Paediatrics, 2003; 23:121-128.

13. K?r?s, M. Muderris, T. Kara,

T. Bercin, S. Cankaya, H. and E. Sevil, "Prevalence

and risk factors of otitis media with effusion

in school children in Eastern Anatolia,"

International Journal of PediatricOtorhinolaryngology,

vol. 76,no. 7, pp. 1030-1035, 2012.

14. Mahadevan, M.Navarro, G -Locsin,

H. K. K. Tan et al., "A review of the burden

of disease due to otitis media in the Asia-Pacific,"International

Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology, vol.

76, no. 5, pp. 623-635, 2012.

15. Bluestone CD, Klein JO. Methods

of examination: clinical examination. In: pediatric

otolaryngology.2nd edn. Philadelphia; 1990, 111-4.

16. World Health Organisation.

Report of the 4th Informal Consultation on Future

Program Developments for the Prevention of Deafness

and Hearing Impairment, Geneva, February 17-18,

2000. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/ accessed 16th

Feb 2014.

17. Connoly JL, Carson JD, Roark

SD. Universal Newborn hearing screening: are we

achieving the Joint Committee on Infant Hearing

(JCIH) Objectives?. Laryngoscope 2005; 115(2):232-6

18. Holster IL, Hoeve LJ, Weiringa

MH, Willis-Lirrier RM, de Gier HH. Evaluation

of hearing loss after neonatal hearing screening.

J Pediatric 2009;155(5):646-50.

19. Rivers State Ministry of

Education, Port-Harcourt Nigeria. Information

obtained February, 2010.

20. Olusanya BO, Okolo AA, Ijaduola

GTA. The hearing profile of Nigerian school children.

Intl J Paediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2000;55(3):173-179.

21. . SPSS Version 17.0. Statistical

Package for the Social Sciences, Released 17.0.1(December

2008). SPSS Inc.

22. Prakash A., Binit K., Jasmine

M., Dipak RB., Tilchan P., Rajendra R., etal.

Pattern of ontological Diseases in School going

children of Kathmandu valley. Intl. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol

2008;12(4):502-505.

23. Ogisi FO., Amu OD. Screening

and audiometry in Nigerian school children. Nig.

J Paediatr 1990;17(2):49-53.

24. Karastas E., Karilikama M.,

Mumbuc S. Auditory functions in children at schools

for the deaf. J Natl Med Ass.2006; 98:204-210.

25. Robinson AC, Hawke M, Naiberg

J. Impacted cerumen: disorder of keratinocyte

separation in the superficial ear canal? J Otolaryngol.

1990: 19.

26. Aqueel A., Ibrahim P., Gholam

AD., Azam R., Ali Akbar., Mohammed HN. A prevalence

study of hearing loss among primary school children

in the South East of Iran. International Journal

of Otolaryngology. 2013;(2013): 1-4.

27. Ahmed AO., Kolo ES., Abar

ER., Oladigbolu KK. An appraisal of common otologic

disorders as seen in a deaf population in North-western

Nigeria. Ann Afr Med 2012;11:153-6.

28. Adhikari P. Chronic suppurative

otitis media in school children of Kathmandu valley.

Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2007, 11:175-8

29. Biswas AC, Joarder A H, Siddiquee

BH. Prevalence of CSOM among rural school going

children. Mymensingh Med J. 2005, 14:152-5.

30. Akinpelu OV, Amusa YB. Otological

diseases in Nigerian children. The Internet J

Otorhinolaryngol. 2007,

31. Mathers C, Smith A, Cancher

M. Global burden of hearing loss in the year 2000.

WHO, Geneva. 2003.http://www.who.int/healthinfo/statistics/bod_hearingloss.pdf

32. Amusa YB., Ogunnija TAB.,

Onayade O.O, Okeowo PA. Acute Otitis media, malaria

and pyrexia in the under-fives age group, WAJM.

24(3) 2005: 40-45

|